Comment/Hayati Esen: Although learning lessons from history is a widely accepted notion, it can actually lead us into a misleading cycle. History is merely the perception and transmission of past events through our senses. However, our senses can have a deceptive impact on our perception of time and space. At this point, recalling the fundamental principles of the theory of relativity is sufficient, as time and space are not absolute but rather variables dependent on the observer.

In this context, drawing lessons from history can be misleading concerning our present time. When we evaluate historical events through the values and conditions of our own era, the lessons we derive from the past may lead to incomplete or incorrect conclusions. Perhaps this is why history has not been accepted as a science like the natural sciences, as it does not establish definitive and universal laws.

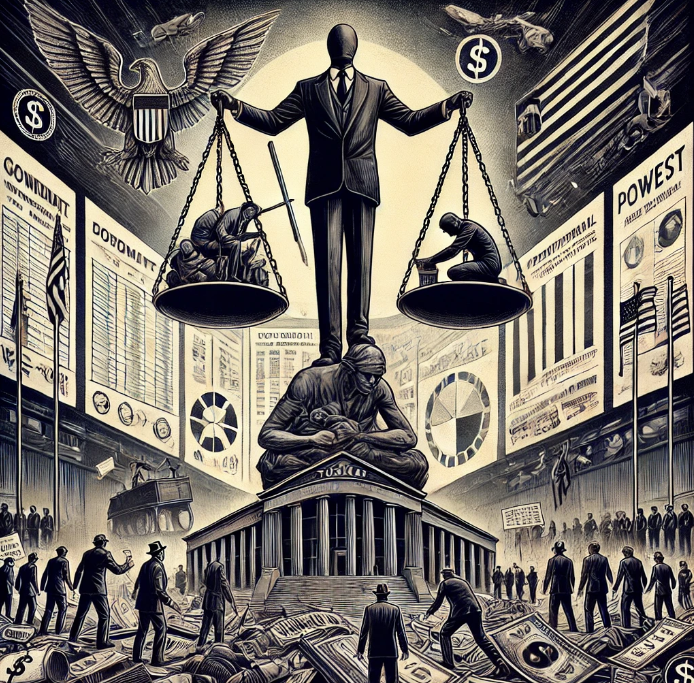

Throughout history, wars, ethnic cleansings, and forced migrations have inflicted great suffering on humanity. Yet, despite claims that lessons have been learned from these tragedies, similar events have inevitably recurred. For example, despite the modern world’s advanced understanding of democracy and human rights, oppression based on ethnic and religious identities still persists. History appears to be a stage where great tragedies are repeated. Even today, it is evident that politicians and leaders interpret past events to suit their own political agendas. The statements of former U.S. President Donald Trump regarding Gaza reflect this tendency to claim lessons from history: “Gaza will be flattened, rebuilt. No one will be there.” These words are not merely a military strategy but can also be interpreted as an attempt to deny a people’s historical existence and erase them from collective memory.

However, one of history’s greatest narratives is that suppressed identities and traumas are never truly erased. Sigmund Freud argued that not only individuals but also societies act according to unconscious motivations. According to him, the human mind is shaped by the accumulation of past experiences in the subconscious, and this dynamic is also valid for collective memory. The collective unconscious is a significant factor that drives historical processes through shared myths, traumas, and repressed desires of societies.

Freud maintained that history cannot be explained solely by rational, political, or economic factors. Historical developments are also shaped by repressed fears, desires, and conflicts. Revolutions and major wars are not merely the result of material conditions but also the external manifestations of social tensions accumulated in the collective unconscious. Religious reforms, ideological transformations, and mass movements, like neurotic symptoms in individual psychoanalysis, can emerge as consequences of deep-seated psychological tensions.

This perspective reveals that learning from history is not a straightforward process of reasoning. When interpreting the past, individuals and societies selectively perceive history according to their unconscious defense mechanisms and historical traumas. Psychological processes such as forgetting, repression, and distortion also play a role in collective historiography. Thus, truly learning from history is only possible by considering these deep psychological layers.

Freud’s theory demonstrated that examining history solely within political and economic contexts is insufficient, emphasizing the need to analyze historical processes in light of psychological and cultural dynamics. This perspective has added depth to historiography by proposing that historical events are shaped by unconscious motivations, traumas, and suppressed desires of individuals and societies, challenging the traditional understanding of history.

At this point, a strong parallel can be drawn between Freud’s psychoanalytic approach and one of the most revolutionary theories of physics—the Theory of Relativity. Albert Einstein’s principle of relativity argues that time and space are not absolute but vary depending on the observer and their reference point. This physical reality can also be applied to the interpretation of historical events. History is often considered an objective sequence of facts; however, in reality, much like time and space, history itself is perceived and interpreted differently depending on the observer’s perspective.

Historiography is less concerned with the past itself and more with how the past is understood in the present. This situation, akin to the Theory of Relativity, indicates that the relationship between historical reality and the observer’s position is in constant flux. An event that is narrated as an act of heroism in one period might be deemed oppression in another. Revolutions, wars, migrations, and social movements acquire entirely different meanings when viewed from varying perspectives over time.

For instance, during the 19th century, the French Revolution was idealized as the liberation of the people and a great victory against monarchy. However, in the latter half of the 20th century, its bloody and chaotic aspects were more prominently emphasized. Similarly, the expansion of the Ottoman Empire was long perceived in the Western world as the tragedy of conquered societies, whereas today, different academic perspectives highlight the empire’s multicultural governance model, presenting a more moderate narrative. These shifts in historical interpretation suggest that while the past itself does not change, our perception of it does—just as the Theory of Relativity predicts, depending on the observer’s reference point.

Furthermore, the relative nature of time underscores the inherent problem of drawing lessons from history. Freud’s psychoanalytic theory suggests that individuals and societies repress past traumas and recall them in different ways over time, while the Theory of Relativity posits that time does not flow universally; rather, each observer experiences time differently. When these two principles are combined, it becomes evident that drawing lessons from history should not be based on fixed and universal truths but should be evaluated within the context of both psychological and historical variability.

History is not merely an objective sequence of events; it is also a relative construct shaped by the psychological tendencies of individuals, the collective unconscious of societies, and the observer’s historical position. Freud’s psychoanalytic approach demonstrates how history is transformed by individual and societal unconscious forces, while the Theory of Relativity proves that historical events do not possess an absolute meaning but continuously change depending on the observer’s perspective. In this context, even the concept of learning from history should be seen not as a fixed and universal understanding but as a dynamic, subjective, and ever-evolving process.

Donald Trump’s remarks on Gaza reflect the contemporary manifestation of the belief that lessons have been learned from history, while simultaneously demonstrating the failure to truly do so. His statement, “Gaza will be flattened, rebuilt. No one will be there,” is not merely a military strategy but also an attempt to deny a people’s historical existence and erase them from collective memory. However, history has shown that efforts to physically destroy and forcibly erase memories may seem like victories in the short term but often lead to entirely different consequences in the long run.

In history’s grand narratives, unilateral victories of power have not been permanent; suppressed identities and traumas have resurfaced even stronger over time. From the Roman destruction of Carthage to the ethnic cleansings of the 20th century, communities that were physically targeted for eradication have clung even more tightly to their cultural and historical memories, sustaining their resistance. Freud’s theory of the collective unconscious serves as a crucial tool to explain this phenomenon: repressed traumas do not disappear but rather gain strength in the unconscious and inevitably resurface in later periods.

Trump may perceive his approach toward Gaza as an assertion of power and victory in the present moment; however, considering history’s cyclical nature and the resilience of collective memory, he fails to recognize that his ideology is, in the long run, bound for significant defeat. History is not merely shaped by weapons or political decisions—it is also driven by human psychology and the unconscious. Therefore, those who fail to learn from history may achieve short-term victories, but these often lead to profound losses in the future.