The NATO Secretary General’s enthusiastic live broadcast of the US attacks on Iran’s nuclear facilities deeply shakes the perception that the war is only taking place within the Israel-Iran-America triangle. It appears that this attack is an operation supported and approved not only by Israel or the US, but by the entire Western bloc. NATO’s position indicates that there is a broad Western consensus behind the intervention in Iran.

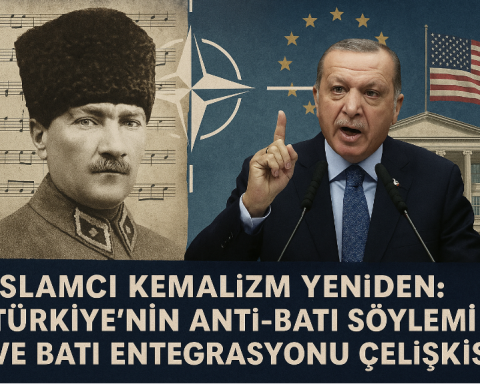

These developments reveal a striking contradiction in the context of Turkey. The political discourse of the ruling AK Party is based on strong anti-Western rhetoric, particularly aimed at conservative and religious segments of society. The narrative that the US and Europe are hostile to Turkey and are trying to divide the Islamic world with imperial projects is constantly reproduced not only in political rallies but also in the media, education, and religious discourse. At times, the possibility of “war with Israel” is even brought up, putting public perception on alert against the West. This discourse serves as an ideological tool to reinforce the legitimacy of the ruling party domestically, while also portraying the opposition as “foreign elements” collaborating with the West.

However, when considering the ruling party’s foreign policy practices, particularly its relations with NATO and the West, a picture emerges that is the exact opposite of this discourse. Erdoğan’s stance at NATO summits represents a line that is compatible with the Western security architecture, integrated with the neoliberal economic order, and open to strategic cooperation with Western allies. Turkey’s defense industry policies, military partnerships, and even its position on migration management reveal that it is an indispensable part of the European-centered system.

This situation shows that political power in Turkey operates on two different levels: while an anti-Western narrative is constructed for ideological consolidation internally, externally Turkey acts as an actor integrated into the West’s security, economic, and diplomatic systems. This dual structure is not only tactical but also ideological, reflecting the ruptures Turkey has undergone in its modernization process. The state’s desire for secularization, centralization, and Westernization is constantly shaped by tension with the traditional-conservative codes of the people. The AK Party, meanwhile, seeks to manage this tension by pursuing a policy of balance that satisfies both its domestic voters and its foreign allies.

This duality reveals a serious disconnect between rhetoric and state reflexes in Turkish politics. The language that consolidates conservatives domestically and the reality that perpetuates a secular state mentality abroad represent two completely opposite lines. This situation naturally brings to mind the concept of “Islamist Kemalism” that I mentioned earlier.

For Islamism, which was influential in the founding of the Republic, is a form of thought that advocates rational thought, scientific thinking, secularization, and state control of religion. Gazi Mustafa Kemal’s vision of modernization was also influenced by this Islamist line. The line stretching from Cemaleddin Afgani to Muhammad Abduh, and from Rashid Rida to Mehmet Akif, actually advocates modernization, secularization, and integration with the West.

Today, NATO’s explicit endorsement of attacks against Iran makes Turkey’s Sunni character within NATO more visible. Turkey has long served as a model country within the Western alliance, demonstrating that integration with the West is possible and legitimate from the perspective of the Sunni Islamic world. In particular, regimes such as the Gulf countries, Egypt, and Jordan use the example of Turkey as a reference point to legitimize their strategic relations with the West to their own people. Thus, the legitimacy of the West in the Middle East is reinforced not only militarily but also on a sectarian level. Turkey’s secular but Sunni identity has become a key factor in its ability to play this role.

In contrast, the Shiite axis—led by Iran, with Iraq, Hezbollah in Lebanon, and even the Houthi groups in Yemen gradually aligning with this line—which has historically been in competition and tension with Turkey, now also overlaps with the Eastern bloc in geopolitical terms. This structure, shaped within the triangle of Russia, China, and Iran, is perceived not only as political but also as a religious-ideological front. The integration of sectarian competition into geopolitical alignments makes every crisis in the Middle East multidimensional.

Therefore, the conflicts we witness today are not merely struggles over energy, military interests, or political influence; they have transformed into a multi-layered struggle where sects, historical narratives, and religious identities are being redefined. Religious and sectarian fault lines are intertwined with new forms of alliance.

Therefore, in order to understand Turkey’s current position, it is necessary to look not only at internal political rhetoric or symbolic moves in foreign policy, but also at the transformation of these historical and sectarian structures within the international system. While Turkey uses anti-Western rhetoric domestically, it can act as one of the West’s strategic tools within the Islamic world internationally. This contradiction can only be explained within a broader historical and ideological context.

Translated into Turkish: https://www.konuyorum.com